Save The Environment 2: I am the .Egg Man

Posted on Sat 05 July 2014 in blog

In my last, bumper-sticker-laden post I offered to share a little bit about the way I pack up my tools for users. This time I’ll try to actually describe the process.

After a all the buildup, I wish I could make this sound more high tech and impressive. Basically, I just pack up what I have and send it all out to my users in a big ol’ zip file. The zip ends up on their Maya’s PYTHONPATH, and gives them exactly the same stuff I had when I created the zip. That’s kind of it. It’s basically a simplified version of a python egg; however since I’m distributing an entire ecosystem in one shot I’ve opted to do the packaging myself instead of relying on setuptools and all of its complex dependency management arrangements.

Simple as it is, this system has saved me a huge amount of time and energy over the last few years. It’s been a long time since I’ve had to worry about a mysterious import failure or the wrong version of a module. Simplicity and robustness are very important, especially in the foundation of a pipeline. Of course, they don’t always make for the most engaging blog posts But I’ll do what I can, even if it means resorting to some pretty lame egg puns.

You can’t make an omelette without…

There actually are some details worth discussing, but before I get into them, I should talk about why this works for the special case of Maya tools - and why it might not work as well for other forms of application development.

My primary problem - the thing I worry most about - is making sure that all my users are running the same code at the same time. Maya tools are hard enough - it’s tough to really nail things down when your data structures are just lying around in the scene where users can poke at them. Between that and the inexorable tick-tock of the game development clock, I’ve gotten very resistant to debugging problems I already solved a week or a month ago and which are only showing up because Jane/Joe Artist doesn’t like downloading the latest tools.

Similarly, it needs to be hard for an end user to delete or mangle vital stuff. I’ve had artists at a former company who decided to “speedup their startup time” by deleting the file that downloaded the latest tools - a fact which only came to light when their out-of-date data started bringing down nightly builds. Most users have a few scripts or tools of their own, but I’m not keen on having unvetted stuff from the intenet being dumped into the same folder where all my tools live - there are lots of ways that can go wrong.

Another thing that’s also important is that the system needs to be clean: it has to be easy to install and to uninstall, and easy for users to switch between toolsets. I’ve got to support multiple teams in house and outsources and I don’t want to worry about micromanaging hundreds of files on other people’s disks.

The last thing I need to do is to keep this system independent of our internal source control. Source control’s real job — managing change over time — is hard enough. Using it as a cheapo distribution service is pushing it into a role it’s not intended for. For one thing, many users have reasons (sometimes good, sometimes bad) for opting out of the daily sync ritual. I don’t want my users dropping out of sync with the rest of the team on purpose or by accident — but I’m also leery of forcing them to sync at a time they didn’t choose, since I don’t know what they’re up to or what other people may have checked in. Plus, we don’t always give outsourcers direct access to source control and I don’t want to have to maintain different systems in and out of house.

Besides, I want to be able to use source control selfishly, to make my own job easier. I want to track my development and have the ability to debug or roll back or branch as I need while working, without worrying that checking in the wrong file will bring my whole team to a halt. I once had a team of 80 artists brought to a screeching halt by a guy who checked in a maxScript file that was auto-synced by everybody in the building. Unfortunately, he did it from a unicode text editor - and Max hates unicode in maxScript. The auto-sync, keep-everybody-current system gave everybody the crashing file straight from his incautious checkin — and, of course, it broke their auto-syncing as well as killing their Maxes. Since then I’ve been pretty leery of using source control to get things into users’ hands.

How to lay an egg

It’s the sum of all these considerations that gives rise to the method I use — which is, as I said, just zipping up a complete environment and distributing that directly to users via a net share or an http server.

The zip comes with a userSetup.py that checks the shared drive for newer versions and grab it if needed and then adds the zip file to the user’s PATH. Rocket Science FTW!

This system satisfies most of my key concerns at a shot:

- It’s all one piece (well, two if you count _userSetup.py). _That means that every user has exactly the same code - and there are no out-of-date .pyc files lying in wait to confuse things.

- Keeping people up to date is automatic

- It can be delivered to a user’s personal maya directory - no need to touch the base Maya install

- It’s outside of source control

- It’s easy to adapt for multiple projects. userSetup can check an environment variable to decide between multiple zips, and the zips can coexist happily with each other.

- It’s trivial to remove: there are no permanent alterations to the local filesystem or the maya installation.

The most complicated bit - and “complicated” here is a pretty relative term - is making sure that the zip file is exactly equivalent to the folder structure I use when I’m developing. My project folder looks more or less like this:

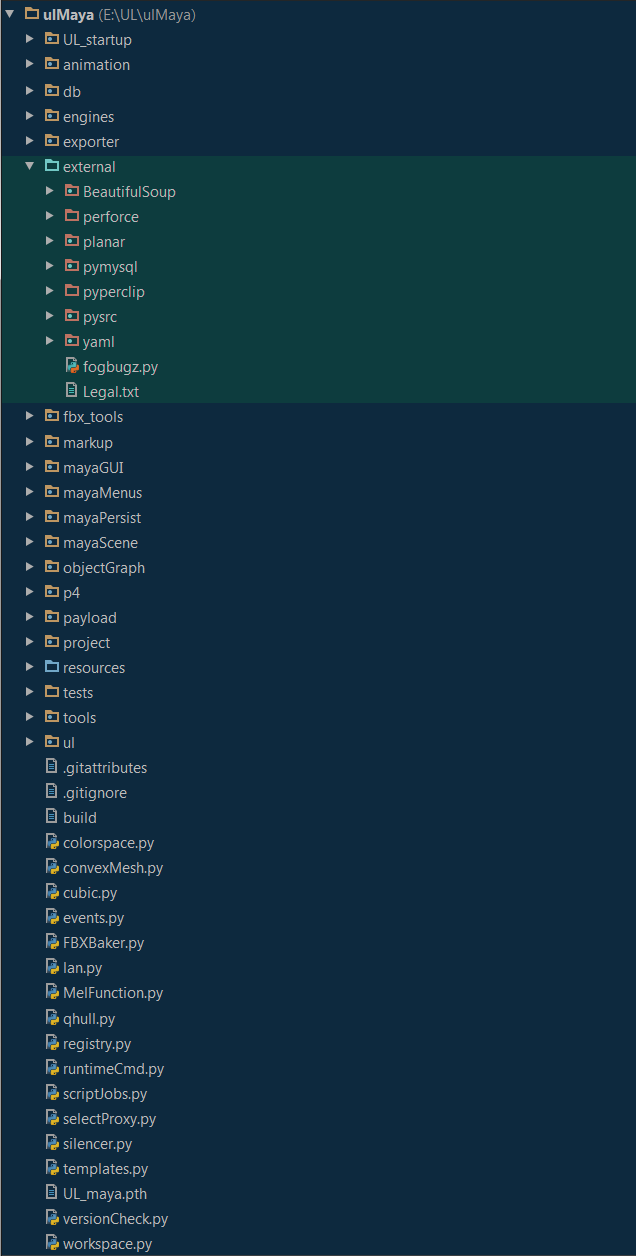

Most of this is what you’d expect: the .py files are modules, and the folders with the little dots in them are python packages. As long as my project folder is on the Python path, these are all available for import in the usual way. The mildly interesting bit are the folders highlighted in green; those are external modules like PyMySql and Perforce, which I keep separately so I can manage the legal mumbo-jumbo that comes with redistributing and licensing. In this example ‘external’ is not a package (note the blue parent folder - my IDE paints them blue if they aren’t on the python path) so none of these packages are going to be on the python path or available for import without a smidge of extra work.

On my own machine, where I’m running from loose files, I add project to my Python path using the wonderful, and often overlooked standard library module site. site is an alternative method of managing your Python search path - instead of appending paths onto sys.path, you can add directories using using site.addsitedir(). The truly excellent feature of site, though, that it’s data-driven: when you add a directory with site.addsitedir(), the module will search the folder for text files with the .pth extension and then add any directories specified there as well. That UL_maya.pth file down near the bottom of the picture is my .pth file: it includes entries for my external modules so that they are automatically included when my project folder is added to the path.

Unfortunately, site does not know how to deal with pth files inside a zip file. So, my startup code includes a little shim which duplicates the functionality of addsitedir. Luckily it’s pretty simple:

"""

ul.paths.py

mimics the site module: process .pth files identically for zip and loose file distributions

"""

import zipfile

import sys

import os

import logging

class SiteProcessor(object):

def __init__(self, root):

self.root = root

def process(self):

for root, contents in self.pth_files():

self.read_pth_file(root, contents)

def pth_files(self):

yield

@staticmethod

def read_pth_file(root, contents):

for line in contents.readlines():

if line.startswith('#'):

continue

if line.startswith("import"):

exec (line.strip())

continue

new_path = "{0}/{1}".format(root, line.strip())

if not new_path in sys.path:

sys.path.append(new_path)

class FolderSiteProcessor(SiteProcessor):

def pth_files(self):

for roots, dirs, files in os.walk(self.root):

for f in files:

if f.endswith(".pth"):

clean_path = (roots + "/" + f).replace("\\", "/")

with open(clean_path, 'r') as handle:

yield roots, handle

class ZipSiteProcessor(SiteProcessor):

def pth_files(self):

archive = zipfile.ZipFile(self.root, 'r')

all_names = archive.namelist()

all_names.sort()

pth_list = [p for p in all_names if p.endswith('.pth')]

for pthfile in pth_list:

local_pth = os.path.dirname(self.root + "/" + pthfile)

contents = archive.open(pthfile, 'U')

yield local_pth, contents

def include_site_files(*roots):

"""

for every .pth file in or under each root, process the pth file

in the same way as site.addsitedir()

"""

logging.getLogger("bootstrap").info("path shim")

for each_root in roots:

if zipfile.is_zipfile(each_root):

ZipSiteProcessor(each_root).process()

else:

FolderSiteProcessor(each_root).process()

This way, adding the whole environment just requires calling include_site_files(). Under the hood the Processor classes will read the .pth files and process them the same way site.addsitedir does: adding named folders to the python path, ignoring comments, and executing imports.

I don’t use that auto-import functionality right now but it would work nicely if you wanted to create a self-registering plugin system where each plugin was a zip of its own. If you were feeling adventurous, you could bootstrap your whole Maya toolset by adding an import statement to the end of a .pth file in the zip. As I said, that’s not what I do right now - I currently call my main bootstrap routine from userSetup.py, since I’m habitually averse to relying the side effects of imports for important jobs.

If (eggs) in one_basket:

It’s userSetup.py that provides the actual link between the zip file and a running copy of Maya. I like to keep it as simple as I can, since it’s the hardest part of the system to update. All it really needs to do is download the latest zip file (from a shared network drive or via http) and shim it in with site.addsitedir. Here’s a very simple example:

'''

This is an example userSetup.py. It should be copied into

one of the user's MAYA_SCRIPT_DIR folders (typically, the one for the

current version, like '2014x64', but it works in the generic one as well)

'''

import os

import site

import sys

ZIP_NAME = os.environ.get('MAYA_ZIP', 'mayatools.zip')

def _startup_(_globals):

tools_root = os.environ.get('MAYA_DEV', False)

if tools_root:

site.addsitedir(os.path.expandvars(tools_root))

else:

script_dirs = os.environ['MAYA_SCRIPT_PATH'].split(";")

for dir in script_dirs:

tools_root = dir.strip() + os.path.sep + ZIP_NAME

if os.path.exists(tools_root):

site.addsitedir(tools_root)

break

import ul.bootstrap as bootstrap

bootstrap.bootstrap(_globals)

if __name__ == "__main__":

_startup_(globals())

del _startup_

You’ll note that nothing is really going on here: just download the zip, add it to the path, and call the bootstrap module. End of story.

This is because you want to keep all the real work inside your bootstrap module. If you try to do anything fancy in userSetup itself, you have to worry about version drift: what happens if the contractor machine in the corner gets turned on after a year of downtime, with a userSetup that’s many versions behind? Moreover, you have no way of preventing users from messing with userSetup for their own reasons: if the code is simple, it’s much less likely to be broken by an adventurous artists.

The bootstrapper module itself is where all of the complex work takes place: it knows how to unpack the binary resources like plugins or icons from the zip file if they have changed, how to turn on persistent scriptJobs , and how to load menu items — all the zillions of things you want to do when you set up you environment. Since it provides a single entry point, it’s a great opportunity to put some order and discipline into your setup process: it’s far safer than importing dozens of tools or modules in a long userSetup that’s not versioned or updated centrally.

You might notice that all the information needed by userSetup is stashed into environment variables. That makes it easy to boot different environments by launching Maya with the right settings; it’s easy to give the users batch files which launch the correct versions of the tools by just setting the variables correctly. This has the nice side effect of supporting nonstandard locations transparently - there’s always that one artist who insists on keeping things on an X: drive to consider. It’s easy to see how this could be done with config files rather than env vars, the logic is so simple that the details hardly matter.

One evolutionary step forward I haven’t used in production is to move the userSetup / zip pair to a Maya module. That would allow for more complex arrangements such as a shared core environment with branch or project specific additions; it would also mean that toolset management would be done by enabling or disabling modules rather than swapping environment variables. The main hassle would be the fact that a user could simultaneously enable more than one toolset and get random results, since you could never be sure which version of a given module you were getting. It might work better as an outsource-friendly mod than as a replacement for the variable-swapping setup.

Hot times in the hen house

The zipped environment is created by a simple Python build program. There’s not much magic here either. The build script runs unit tests and aborts the packaging process if they fail. If the tests pass, the builder gets the latest versions of any external resources (like icons, or binary plugins), and strips out some stuff like unit tests that doesn’t need to get to the users. I add a little bit of metadata — basically, a text file — to the zip so I can quickly find out which distribution is running; this is a great way avoid those headsmacking “I fixed that bug a week ago, but user X hasn’t restarted Maya in two weeks” mysteries.

One nice refinement that we discovered almost by accident is using the py_compile module to pre-compile the whole shebang before packing. Our system ships only pyc files instead of pys. This speeds up load times and slims down the zip file by a noticeable amount. However the most important thing it does is make sure that every module - even those with no unit tests, which are alas too numerous - is at least minimally importable. py_compile will complain if it encounters a module with a syntax error that cannot be compiled. Over the years this has saved me countless small humiliations by making sure that stupid typos and oversights don’t result in a busted Maya.

These days I use a little python program which polls my GitHub repositories for changes and tries to create a new build when a checkin is pushed to the master branch. The server handles running multiple builds for different Maya versions: When Autodesk rev’ed the version of Python inside Maya, it meant that we needed different .pyc’s for different versions of Maya. For most of the last several years, though, I simply used a zip script from a command line or as an external tool in my IDE and that answered fine for most purposes. Moving to a server is just a way of making it more painless for a team to do the right thing automatically instead of appointing one person as ‘build master’ and making them sync and push the button to start a build.

Extra credit: Can you guess who the build master was, and why he decided to write the server?

Hatchlings

One problem I don’t have to solve for this application - but one which looms very large in the setuptools-distutils-easy_install end of Pythonland - is dealing with a diversity of OS’s and hardware. I’m happy not to try to deal with things like recompiling a slew of C extension modules for DEC-Alpha chips running OS/2 or whatever. I’ve only got Windows users currently (though pretty much everything I write works on OSX, since I often develop on my laptop). This removes, for me, the primary appeal of the traditional python distribution pipeline, which is the option of automatically creating whatever esoteric binaries you need just by typing a few lines at the command prompt.

The price for not letting users compile on their machines is that I have to pre-package the right binaries. To the extent that I can, I end-run around the problem by using pure python modules in preference to binary alternatives, such as using PyMySql in preference to MySQLdb, or elementTree instead of lXml. Inevitably, this does give away some performance (rarely so much that I’m bothered by it) but it hugely enhances portability. The unavoidable exceptions are things like Maya plugins or the Perforce API, both very finicky about OS and bit-depth; these have to be distributed as part of my zip files and extracted at startup time. The bootstrapper module includes a manifest which tells it which files to use for which Maya/OS/bit-depth combination, and uses that info to makes sure that things get delivered to the right place.

The only complication I’ve run into is that a user (often, me) is may be running multiple maya sessions, and a later one may want to unpack a new version of a binary plugin while an older session is still using a previous version. Unsurprisingly, you can’t overwrite the old one since Maya is using it. I haven’t quite figured out what to do in that situation, beyond displaying an error dialog and suggesting that the user restarts all of the Maya instances using the same plugin. For the time being the overlap between tool changes and multiple Maya sessions is rare enough that I tolerate it. It would be possible to dump things into a temp directory in that case, but honestly it sounds like overkill even to me.

Counting your chickens

So, that’s kind of it. It’s not very sexy but it’s been extremely useful for me over the last 4 years - the amount of mystery which this system removed from my life is uncountable. Because the actual code I use is pretty tied up with work-specific problems, I have not ventured to make a cleaned up, genericised version for public consumption so far, though if there were a lot of interest I could probably whip up a cleanroom version.

Hope other folks find this one useful. I know it’s certainly ~~accompanied~~ saved my bacon !