How the other half lives, revisited

Posted on Thu 22 June 2017 in blog

Way back in 2013, when I was first getting this blog rolling, I spent some time investigating different ways to get Python into the browser. In the intervening several years, Javascript has continued to spread its dark cloud of despair over the web like a digital Mount Doom, spewing depression and silent type conversions to every corner of Middle Earth.

The much-hyped prospect of WebAssembly hasn’t really panned out yet. There has been progress, and someday we’ll probably get to the point where Python and other languages can be ‘compiled’ directly to WebAssembly — but right now the tools and processes for doing it are pretty clunky and the performance of Python intepreters running in the browser remains unimpressive. The most successful project in this space — Pypy.js works pretty well. But, because it’s a port of the whole CPython interpreter, it’s a huge download: on my fast connection it takes 11 seconds to load and boot the Pypy.js interpreter for the first time. Pypy.js is a hopeful sign, since it’s extremely compatable and, startup times excepted, not too slow to run. However it’s going to be a while yet before somebody figures out how to cut down the huge cost of importing a whole python ecosystem into a browser.

A different approach approach which has prospered in the last few years is the creation of dialects of Javascript which work around some of the language’s quirks and syntax. Effectively, you write in some other language and then compile (or more precisely, “transpile”) it into Javascript. This approach has two obvious benefits. First off, you get the universality of Javascript — once your code is transpiled, it’s just another bit of JS so it will work in all sorts of browsers without extra help. Secondly, it’s automatically interoperable with all the Javascript libraries out there, so you can tap into web ecosystem right off the bat.

One of the first examples of this approach CoffeeScript, which looks and acts a lot like Ruby but gets turned into vanilla Javascript when compiled. I did a couple of hobby projects with a more Python-ish transpiler called RapydScript, which bills itself modestly as “Pythonic Javascript that doesn’t suck”. For a lot of common cases Rapydscript really looks and acts like Python. However if you’re a moderately advanced Python programmer the two languages start to show increasing differences; the maintainer of RapydScript wants to optimize for raw Javascript performance, which means that many language constructs don’t work quite the same way; the project’s list of “quirks” ended up being a little long for my taste.

Transcrypt

You can tell it’s a real project because it’s got merch!

The most recent entry in the transpiler field is Transcrypt. Like other transpilers it allows you to write “almost Python” (in this case, “almost Python 3.6”) and compile it to Javascript. For me, at any rate, it has a couple of interesting advantages to other entries in this space:

Source maps

The most irritating part of using a transpiler is debugging. By definition, there’s not a 1:1 match between the code you wrote and the code that’s being run, which usually makes it tricky to understand how things have gone wrong.

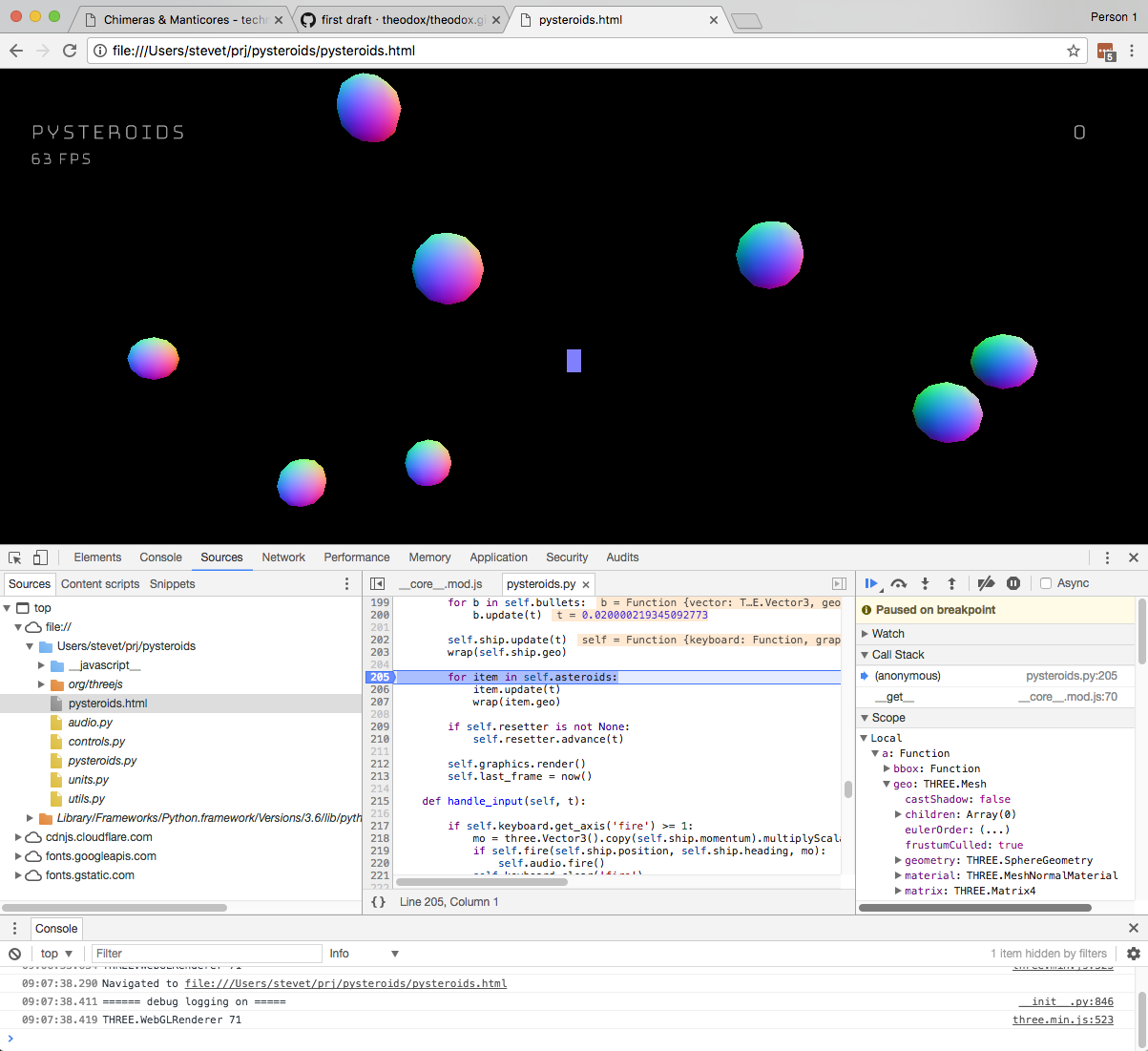

Transcrypt makes this far less painful by generating good source maps, which provide a map between the compiled code and the source. This feature was created to support ‘minified’ JS (where all the whitespace is removed to allow for quicker downloads), but Transcrypt hijacks it so that runtime problems in the JS version point to the python source when debugging. In Chrome, at least, I can even get live preview of the values at a breakpoint:

Debugging Pysteroids.py in Transcrypt and Chrome.

For me this is Transcrypt’s killer advantage over alternate transpilers: it means I can debug as well as code in Python.

Occasionally the problems are in code that doesn’t map easily to mine, in which case I’ll see the Javascript debug code instead. Transcrypt’s JS is generally clean and readable, although (being Javascript) it still involves spooky scope magic that my brain refuses to process properly. It’s true that things get funky when you start descending into code from Javascript libraries — in the shot above, for example, all of the graphics are rendered three.js — so one occasionally gets shunted into unreadable minified library code. Still, so far I’ve found Transcrypt’s source mapping combined with the Chrome debugger is a pretty good productivity environment; it’s at certainly more sophisticated than dumping print statements into the Maya listener!

Fine-grained control

There’s a built-in tension in all transpiled projects. A lot of core language features in Python have only approximate counterparts in Javascript; basic data types like lists (= JS Array) and dicts (= JS Object) have related but still distinct behaviors. This forces the transpiler designer to choose between re-implementing the Python behavior in a custom JS object — which is going to be slower than using the native JS types — and creating false-friend code which confounds the user’s expectations when run in the browser. Rapydscript basically followed the designer’s intuitions as to which behaviors to keep and which to branch, so perhaps it’s not surprising that this has led to a rival fork of the project from a developer who disagreed with some of those choices. All translation involves compromises: as they used to say “traddutore tradditore”, “a translator is a traitor.”

Transcrypt tries to resolve this tension by allowing more local control over the compilation strateg. You can opt in to the more expensive or intrusive features using compiler directives. This moves more of the burden onto you, but it at least allows the choices to be made tactically rather than making you work in a predetermined way.

So, for example, an ordinary Transcrypt function does not accept the **kwards syntax. However you can enable it in functions where it’s appropriate like this:

def vanilla_function(*args):

print ("*args are supported automatically")

__pragma__('kwargs')

def kwargs_function(*args, **kwargs):

if kwargs['test']:

print ("kwargs have to be enabled manually")

__pragma__('nokwargs')

I could be happier about the aesthetics of all those __pragma__ statements lying around but at least they are explicit. One quirk I did find a bit tough is that it’s not always clear where the __pragma__ really wants to reside: so, for example, I wrote a litte coroutine generator that needed to use the send() feature of generators. In Transcrypt, that is only enabled with a pragma, but it took me a couple of hourse of confusion before I realized the pragma had to be present where I called send(), not when I created the generator.

Nevertheless, I do like the idea of having opt-in control over the more expensive or complex features of Python. Not only does it let the user make personal tradeoffs between Pythonicism and performance, it also helps to teach you where the real differences betwee pure Python and Transcrybed Python lie.

Pythonic feel

This aspect is subjective, but in general I’d say Transcrypt feels more “pythonic” than Rapydscript. The compiler is actually written in Python and uses the native Python AST module, so it does not have to reinvent the semantics of the Python side of the language. It’s got most of the things that make Python a high-productivity environment — classes, list comprehensions, decorators, even metaclasses. I’ve run into a few gaps in the toolkit — for example, at present a metaclass can’t create an instancemethod for you — but I’d say that at least 9 out of every ten things I try using my Python instincts work as expected.

Gotchas

Of course, there is still a residue of gotchas. Javascript is a language (and one with many notorious quirks of its own) and not a neutral platform. So, Transcrypt inherits some of Javascript’s less… useful… behaviors in ways that can trip you up. The nastiest one is JS’s habit of silently changing types for you. I never really got the point of those forum trolls who insist “Python is a strongly typed language” until I started getting bugs that came from this behavior. Sure, you don’t need all the scaffolding of C# or C++ variable declarations in Python, but a number is still a number and a string is still a string. In JS, well… maybe not. In Python

print (1 + "X")

will raise an error:

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

but in Javascript — and in Transcrypt — it just prints “1X”. This leads to an awful lot of deferred bugs, where code just continues skipping merrily along long after it should have crashed because you passed in the wrong kind of variable. Transcrypt actually supports the new Python type annotations, and it provides a linter that will help you spot possible type errors at compile time. That’s helpful but it’s still not what my Python radar is scanning for.

There are also parts of Python that haven’t been ported. The two that I’ve been bummed out by are context managers and descriptors, both of which I miss. I’ve bumped into the limits of the port once or twice as well — for example the Transcrypt zip() works as expected for static lists but doesn’t work with iterators or generators. On the plus side Transcrypt is open source so it’s not unlikely that some of these gaps will get filled. However it’s important to recognize that Transcrypt isn’t intended to be a complete Python: the project’s goal to combine high — but not complete — compatibility with speed and simplicity. Completists will probably find it frustrating, but pragmatists will probably enjoy what it can already do.

Report Card

Despite the missing pieces, I like Transcrypt pretty well so far. It’s not a complete web-ready Python, but it’s a lot more fun and productive for me than writing JS. It only took a few nights to bang out a version of Asteroids with Transcrypt and three.JS which runs pretty smoothly on my phone with 3d graphics and audio. You can play it here. You’ll note that I didn’t push it too far — you’ll need to reload the page after you clear the level or die three times. My high score so far is 9583, if you’re feeling competitive. I did, however, include the source maps along with the minified, transcrypted Javascript — in Chrome, you can see the original Python by opening developer tools and looking at sources. The code is also up on Github, although it’s not the most interesting part of the process: getting a working Python game into browser is the cool part here.

I don’t think I’d be substantially more worried about tackling a bigger project in Transcrypt than I would be to do it in JS, though that probably says more about my lack of JS-fu than anything else. On the whole, it’s a fun and useful piece of kit. Although the missing bits and pieces are irritating, I’m not altogether sure they’re actually more irritating than the hassle of creating a working virtualenv with pyglet or pygame would be. And — unlike pyglet or pygame — once I’ve got my project compiled I can get it into lots of people’s hands by simply popping it onto a web server without any of the usual indignities of Python distribution.

So… it’s not quite web-python Nirvana but it’s pretty damn cool.