Just Put One Foot In Front of the Other

The humble walk cycle is the foundation of the animator’s art. A really good cycle doesn’t just move a character from place to place: every cycle ought to be a highly compressed character study, as concise and elegant as a haiku. The climax of Toy Story, where Woody and Buzz race after the moving van, is a brilliant example of two characters doing the same thing, and yet doing it in ways that are perfect expressions of their respective personalities.

All too often, of course, the demands of production get in the way of the poetic ideal. Between the technical demands of game engines and the casual disregard which designers and players share for the laws of the universe, the harried game animator isn’t always going to have the opportunity to carve out that gem-like slice of time that describes a character.

Naturally most animators prefer a visual to a verbal reference for something as complex as a moving human being. In an ideal world we’d have the chance to perfect our knowledge with lots of reference footage, mocap data, and observation time. That’s the classical approach, going back to the days of Disney’s Nine Old Men, and any animator who can should pore over video , mocap, and Muybridge when time permits. Even so, it’s good to have a little cheat sheet handy for those times when there’s no authoritative reference lying around. In particular, it’s nice to be able to give designers and coders some real world facts about how human locomotion works for those delicate little negotiations around things like character speed. With that in mind, we’ll going to borrow a little science for this look at locomotion.

If you’re researching the mechanics or physics of walking, you’re likelier to end up reading medical journals than back issues of Animation World – most of the reference work on the web comes from academic researchers, not artists. From choreographers to fossil hunters to orthopedists, the study of movement on two legs is a busy field, so at least we’ll be able to borrow a little bit of terminology and some useful numbers from our scientific friends (some useful references can be found in the sidebar). Of course our real interest s are art and drama, not science; so don’t be enslaved to any figures cited here. Never forget the tried-and-true Pixel Pusher rule: Do what looks best to you, not what some book or magazine column (however witty, erudite and trustworthy it may be) tells you.

Any movement cycle can be defined by four basic components:

• Gait: the pattern of footfalls

• Cadence: the timing of the strides

• Stride length: how much ground is covered by each pace.

• Stride width : often forgotten, but an important key to the style of a cycle

You’ll notice that the obvious game play element, namely ground speed, isn’t in this list. As we’ll see, the speed of a cycle is produced by the interaction of the cadence and stride length; by itself, the speed doesn’t tell you enough to distinguish one walk from another.

Walk, Don’t Run

Move cycles come in two basic flavors: walks and runs. As any animator knows, walks contains a moment when both feet are on the ground at the same time, while in runs only a single foot is ever supporting the body. The mechanics of the two movements are quite different as well. As every animation tutor since Seamus Culhane loves to repeat, a walk is a “controlled fall” – the walker pivots over the “down” foot like an inverted pendulum using a minimal expenditure of energy. A run, in contrast, uses the raw power of the planted leg to essentially jump from foot to foot. This is why jogging is better exercise than walking even though a brisk walk may be faster than a slow jog: walking is a more economical way to get around and running, even a slow run, is more forceful.

The shopworn game industry convention treats “walk” and “run” as different speeds, rather than different ways of moving. It would, of course, be more flexible and realistic to cover a range of speeds. Unfortunately, we can’t achieve this just by blending walks and runs together: the mechanics are quite different and there’s no such thing as having “one and a half” feet on the ground. However, there is a lot of natural variation within the two gaits, so it is possible to cover a broad range of speeds by creating fast and slow versions of both the walk and run gaits with some overlap in their speed ranges.

Working with speed ranges, rather than single speeds, does involve some work on the code side. Tom Forsyth’s 2004 GameTech presentation How to Walk gives a good overview of the technical issues involved. For the artist, job is in some ways easier than authoring two fixed speed cycles. Since the actual runtime speed of the character will be the product of a blend, animators can work on artistically clear extremes without waiting for design to settle on the character’s speed down to the last decimal place. Doing two runs or walks also encourages animators to emphasize the character aspect of the cycle over the mechanics, since precise ground speed is less of a constraint.

Hup Two Three Four

Of course many game engines already have a rough-and-ready mechanism for adjusting the speed of a move cycle: they slow down or speed up the default walk and run cycles.

Although this makes intuitive sense – moving slower or faster would certainly seem to mean stepping more or less quickly – it’s actually unrealistic. You can see proof of this very easily by watching army drill maneuvers: A typical quick march step uses a 5 foot (1.52 m) stride once per second (when the drill regulations were standardized in the 19th century that was a big purposeful step, but for today’s taller soldiers it’s a fairly natural pace.)

When the formation wheels around a corner, you’ll notice that the soldiers on the outside of the formation, who have to cover much more ground than those near the pivot, never break the rhythm of the march – they simply extend their strides to about 5’6” (1.67 m) to keep up with their ranks. The overall rhythm of march never varies (see around 0:40)

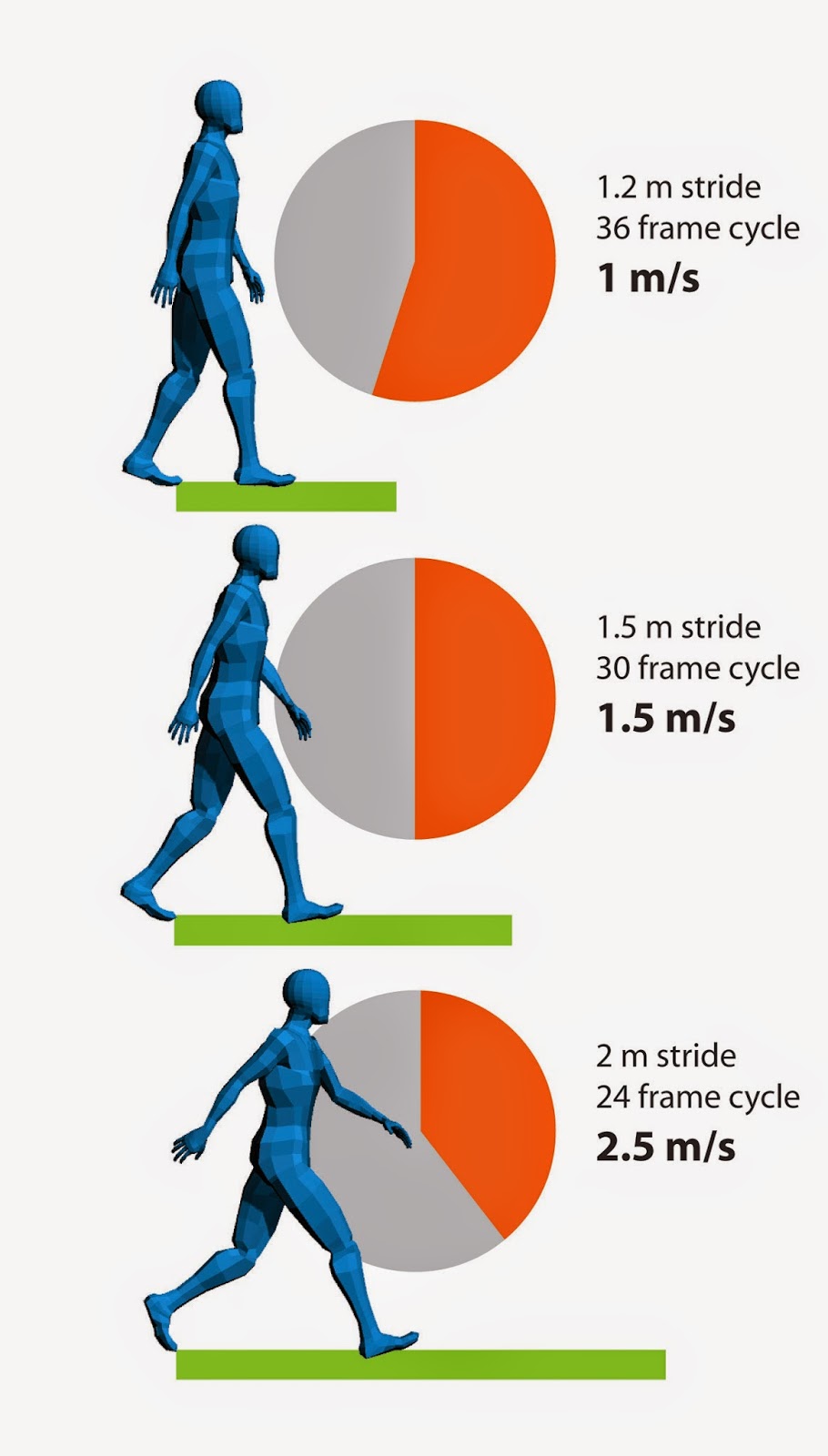

This image gives a good general idea of the relationship between cadence and stride length at different walking and running speeds.

As you can see, variations in stride length account for more of the speed changes than changes in cadence: the brisk walk covers 2.5 times as much ground as the relaxed walk, but only 33% quicker. This suggests that blending different stride walks is a more realistic way to adjust a character’s ground speed than just adjusting playback speed. Blending cycles with different cadences is a bit of work for coders but it makes life much easier for animators. Trying to create two walk cycles that cover quite different speeds but in the same amount of time is far harder than finding a combination of timing and stride that works both for the character and the specified speed.

Establishing a cadence is obviously critical to building a good cycle. Since ground speed is the interaction of cadence and stride length, it’s important to find a combination that matches the character and not just to settle for one that “works” to move the character across the ground at the right velocity. Faster cadences imply excitement, hurry, or anxiety.

Slower cadences tend to suggest relaxation, fatigue, reluctance, or solemnity. The army, for example, reserves a special 60-step-per minute (ie, 60 frame) step for funerals and memorial services. Interestingly, though, cadence is not a good indicator of age: one famous study found that runners in their 80’s step at about the same cadence as those in their 30’s. They do, however, cover far less ground with each stride. They also spend more of each cycle firmly on the ground, and less of it pushing off or bounding through the air.

Those geriatric marathoners illustrate an important rule to for working with movement cycles: cadence and stride length are hard constraints that have to be met, but that leaves a lot of room for individuality within the rhythm of the cycle. The point of balance, height of the vertical bounce, and side-to-side hip sway are all important to the character of a run or walk. The depth of the “bounce”, in particular controls the character sense of weight and energy level as well. Keeping that movement separated out from the gross movement of the character across the ground (as we discussed in The Conquest of Space) makes that a far easier variable to control.

Daddy Long Legs

Stride length is an important determinant of speed, so it’s important to remind your concept artists and designers about it early on. Even small changes in a character’s physique can make a big difference in his or her stride length, thus the range of plausible speeds. Track and field coaches have a rule of thumb that a human’s stride length is about 83% of their height ; thus a typical 6’ (1.82 m) game character would have a stride length of just over 1.51 meters. Combined with the common 120-steps-per-minute cadence this gives a “natural” walking speed for a human character of around 1.5 meters per second, which is the figure you’ll find in many web references. A 4’6” (1.37m) dwarven warrior, on the other hand, has a natural stride length of about 1.13 meters. Unless he’s get very different proportions he’ll have to scurry to keep up with that six foot comrade: to match the human’s ground speed the dwarf will have to have about a 22 frame walk cycle, or more likely break into a run.

Although stature has a lot to do with stride length, it’s not the only factor. For example, that track coaches’ rule of thumb says a man’s stride length is 83% of his height, but a woman’s is 82.6% of hers (who knew track coaches were so precise? —ed). Women, however, have proportionately longer legs than men, so the difference there is one of musculature and usage. Race walkers may have a stride length that’s more than 90% of their height, since they’re willing to look silly in pursuit of speed:

On the other hand children and older folks tend to use less of their potential stride because they’re less sure of their footing. The very young and the very old also have a tough time keeping their stride lengths consistent – toddlers can vary their steps by as much as 20 or 30%, while by the mid teens most kids maintain their stride length down to the millimeter.

Not surprisingly, the flexibility of stride length is the animators greatest friend in the run cycle business – it’s hard for a human character to look anything but silly if the cycle is much faster than 14 frames (a fantastic 260 steps per minute) but it’s comparatively easy to add a little extra flight time to achieve the impossible speeds so beloved by designers. One useful tip when extending strides beyond their natural limit: don’t over extend the forward foot, instead shorten the plant and increase the kick of the back foot. If the angle of the front leg at strike time is 45 degrees or lower it wants to be a brake, not a lever.

Striding Wide

Those long strides convey confidence, drive, and assertiveness. Shorter steps suggest caution or timidity – it’s why we call them “baby steps”. They’re also the way we adapt to complex or crowded environments. The tension between confidence and caution is also reflected in the width of moving stride, a detail that animators often forget. Children, the elderly, and the infirm walk keep their feet spread wide to help maintain balance, as does anyone who has to cope with uncertain terrain.

Narrower gaits are a sign of self assurance: both Olympic sprinters and supermodels place their feet very close to the centerline of the body as they move along. For the runner this is a matter of efficiency, since the thrust that pushes the body along works better close to the line of movement — although sprinters start with their feet about 15” apart, roughly in line with their hips, by the time they reach full stride 9 or 10 steps into their run their steps are less than 7” wide. In the case of supermodels, the narrow track width accentuates the sway of a woman’s hips (already wider than a man’s) and helps emphasize her femininity. In both cases, however, the compact posture reflects confidence where a more open stance anticipates potential difficulties.

Reference data

Here are some reasonable real world numbers from a variety of sources. As always, your eyes should be your guide; but these numbers form a good starting point.

Ground Speed (meter/sec) | Ground speed (mph)| Stride Length (meters)| Cadence (steps/min) | Frames (30hz) |

—-|—-|—-|—-|—-|—-|—-

1 m/s | 2.23 mph | 1.2m | 100 | 36 | Deliberate walk

1.5 m/s | 3.35 mph | 1.5m | 120 | 30 | “average” walk

2.5 m/s | 5.59 mph | 2 m | 150 | 24 | Brisk stride

1.6 m/s | 3.71 mph | 1.33m | 150 | 24 | Slow jog

2.7 m/s | 6.03 mph | 1.8 | 180 | 20 | Easy jog

4.5m/s | 10.06 mph | 2.7m | 200 | 18 | Distance runner

11.2 m/s | 25.05 mph | 4.8 m | 280 | 13 | Sprinter

For comparison, here’s a few game numbers. You see why I said designers tend to ask for unrealistic speeds. Athletes and very nervous people can hit many of these numbers — briefly — but most of them can’t peg a quickscoped headshot at the same time.

| Game | Player run speed | |

|---|---|---|

| Max Payne | 5.5 m/s | |

| Jak And Daxter | 6.6 m/s | |

| Halo | 6.86 m/s | |

| God of War | 7.5 m/s | |

| Unreal Tournament | 8.8 m/s | |

| Quake Wars | 8.94 m/s | |

| Serious Sam | 12.5 m/s | |

| Quake4 | 15.25 m/s |